Louisville's original rock scene is blossoming, with new bands being born every week. The scene is growing like a forest, with rich underbrush readying the way for trees. Every four or five months, a particularly promising sapling emerges that sets the Louisville music community buzzing.

In November, everyone was talking about Smokehouse, which, it was whispered, is an all-star group fronted by an already-signed rock singer from England. Todd Smith, the respected keyboardist from the late Domani, was in the band. So was Chuck Mingis, the popular guitarist from Spanky Lee. The drummer was none other than Matt Thompson, the HammerHead drummer who wasted no time in lining up gigs with Henrv Lee Summers and other mid-level luminaries after that regional band's breakup. The bass player spot took longer to nail down, with Robert Marston falling in two months before Smokehouse's debut.

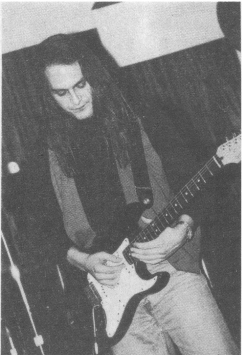

At the Rough Diamond Music Network's Original Showcase on November 3, the quintet took the stage at the Phoenix Hill Tavern for the first time. No one knew what to expect, but few were prepared for the kinetic blend of painfully straight-ahead rock, sweaty soul, honky funk and sweet pop. "Let's Roll," their first song, skirted past a Sammy Hagar-like fist of rock, pummeled pliant by sixteenth notes from Marston's fretless bass Smith's Hammond B-3 organ massaging the heart, taking the jagged razor of Mingis' guitar and giving it the promise of organic peace and healing. Thompson, as usual, drummed like a clinician, only better many have heard Thompson execute gigs, but this time it was with the consideration that marked his HammerHeads work.

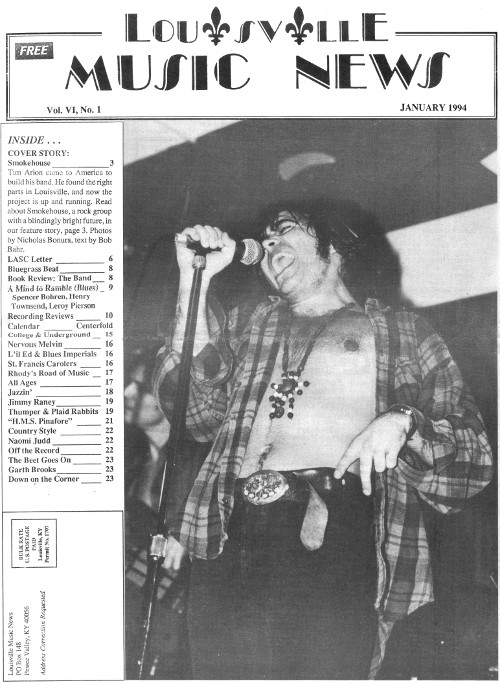

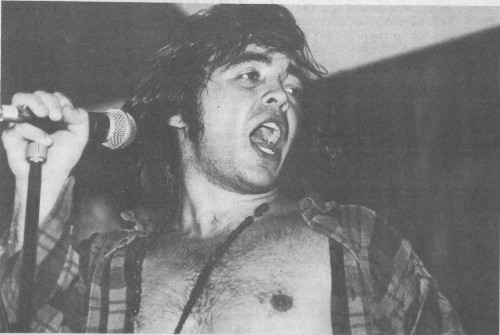

And the Englishman, the mystery man who was bringing these musicians together, wore the crowd out with his 100% effort at the vocal microphone. Tim Arlon's hands alone worked harder than most front men, gesticulating like an updated Robert Plant, Arlon's bare chest jutting out in a cocky, Mick Jagger manner. And out of his throat came a just-sweet-enough rough belt, like the pupil in Otis Redding's class that outperformed Chris Robinson.

The audience was stunned, save a few hard-core alternative music-heads. We'd heard an energetic rock band before. We've heard great bassists, solid drumming, meaty lyrics, blue-eyed soul vocals. We even know the B-3, although the instrument's sheer bulk makes its appearances rare. What set aside Smokehouse was the perfect execution of all that stuff, the professionalism. The focus, the singular tone.

"I don't think we're really apart from all the other bands," said Mingis, blowing off the praise in an interview a few weeks ago in the band room of the Butchertown Pub. "We're just another band."

There was a pause, then Thompson offered, "I think the only thing we have is an outside influence coming into this area. Tim being from England, that's a whole different attitude and environment. And that being brought into our playing ... that, to me, is such an uplift."

"And what you guys do to me is totally new and fresh," responded Arlon.

When Louisville Music News caught up with Smokehouse, they were hours away from their fifth show. Band members, together no more than three months, exhibited the courteousness typical of new friendship.

There were unwarranted apologies, polite disclaimers and a deferment to Arlon on most questions. Arlon, for his part, exhibited enthusiasm, rebelliousness and an inkling of PR polish. The irrepressible Thompson offered constant wisecracks and spontaneity. Marston was missing and Mingis was reticent.

Smith said, "For an England man, you're very Americanized. You're not all, [imitating a British accent] 'Oh, tea and crumpets.' You're more, [imitating a country accent] 'Gd, give me a beer.' He's like one of us in sort of a soul-brother kind of way. So musically, we meet up. Obviously, there are cultural differences, because we grew up on different continents. But in a way and correct me if I'm wrong in his music, even back in England was American-sounding. Kinda blues-based, soul-based. Almost like he has always been drawn to America, to the South sound that we have. And now he's here. You know, sort of like John Denver 'Coming home to a place you've never been before.' [Laughter.] Do you have that feeling?" Smith asked Arlon.

"I do, actually, because I've always loved America! Most music that I really remember growing up on was from the '50s," said Arlon. "It sounds weird, being 21, but I was a total Teddy Boy. I had a coif. I wore leather pants. Big. pink shoes - big-soled things. Tight leather pants. Green, sequined jacket. Elvis Presley. I had a huge collection of '50s albums. That was the first music I ever got into. Then it was blues and jazz. And then recently, rock 'n' roll. English rock, which I never was into. I hated it. l got into it because I was with my band."

You see, Arlon has been in this kind of situation before. Sixteen of the 20 songs currently in Smokehouse's repertoire have been played before, in England, with another band.

Arlon was signed to Imago Records, a major label, because of the strength of his songs. Imago didn't like Arlon's band, even as it garnered praise and popularity in London. There are better players in the U.S., they told him.

So Arlon broke with his band, signed on with Imago and came to America with one major lead: Domani. Arlon had helped out on the Louisville-based band's recording sessions in Los Angeles. He knew Smith's talents. He wanted Smith in his band.

Imago persuaded Arlon to look in L.A.,New Orleans and New York for his group first. He didn't find right people; perhaps the strong-willed Arlon never intended to find the right people. In July, Arlon followed his instincts and came to Louisville, assembling Smokehouse under Smith's guidance.

The transplanted sapling thrived in Louisville.

"Tim's songs, I hope this is fair in saying this, need to be grown on American soil," said Smith. "We gave it the feel that it's meant to have. He tried to run those songs through the England band and he said that it lacked it didn't sound like it was supposed to. And now his songs sound like he meant them to sound."

"That's absolutely correct," Arlon said. "I would try to explain what I heard in my head and they wouldn't have a fing clue. I don't have to say it here because it's a natural thing. It's what is evident. They'll just listen to something and they will play it that way anyway.

Specifically, what do these Kentucky boys bring that is different?

"Soul and truth," said Arlon. "It's something they've grown up with, growing up in the South. There is, to me, an outlook, a very Southern way. It's very laid back. It's in a groove. It's a natural rhythm of life that's so different from England."

Tongues wag in music circles. What happens if Imago doesn't like this batch of musicians either? Arlon said there's no comparison.

"There's a huge difference," Arlon said. "A) The guys [in England] couldn 't play anywhere NEAR what these guys can do. B)They didn't have the soul that any of these guys have. D) They didn't have the focus that these guys have." And C) [Laughter among the band at Arlon's cockeyed alphabetical order] It was a totally diffrent thing.

"They would play the notes that were in the songs," he continued. "These guys [Smokehouse] it seems as though there are no notes. It's just feeling and it's soul and it's what is coming out. When you listen to the tapes from England, you hear the technical guitar bits and a drummer who was really he was I a pretty good drummer, but he wasn't very technical or anything and he was just trying to hold the beat down. The bass player was very good. But the compilation of those three really didn't add up to anything solid and focused and amazing. My feeling about these guys is, I'm totally blown to fing s. In every way."

The president of Imago Records saw Smokehouse at their MERF appearance on Nov 21 A top-level executive from Warner Chappell, the song publishing giant, was also in attendance Arlon's father was there too a man who has nurtured the career of a number of pop music superstars.

What was the verdict? In a nutshell they came down - the big guy [from Imago] came down - and said, 'Yeah, it's good. Let's tweak this, work on that and I'1l come back and see you guys in February," Smith said."He's keeping the support coming. He didn't come down and say, 'Okay. We're ready to do the deal.' But he did come down and say, 'Let's work on this and that. And if you get this or that right, then we'll talk.' Continued Smith: "We sort of got a little bit of the record company 'yank,' in that they said to Tim, 'Okay, we'll sign you up. Now go and put your band together.' So he came here and did that. We got the show, invited them down and said, Okay, here's the band.' And they said, 'But...you...don't...look...like you grew up together."'

Thompson: "Hellooo!"

Smith: "What do you expect?"

Arlon: "I find a lot of the image thing that bands have to go through changing haircuts or whatever is bs. If you can't get up on stage and be yourself, I think it's crap."

Mingis: "It shouldn't matter."

Arlon: "Yeah, that's the thing. It really shouldn't matter. You know what I mean? Unless people want to look at the band like . . . I suppose the whole idea of image is for people to look up at the band and say, I want to be like that.' 'I'd like to dress like that "'.

Mingis: I think the thing is, they want the and look like a band."

Arlon: As if everybody knew each other and grew together/ lt's such a shame, but we have to. That's the job that we have to do.

For an hour and a half on stage, it's not really worth being a pain in the a about, really, is it?" The short, stocky vocalist knows it's all part of the game, but he clearly has his limits.

"One of the things about us is, I don't think any of us are depressed, philosophical guys, you know," Arlon said plainly.

"When we get up on stage, we enjoy ourselves and we smile and we have a good time. A lot of the reaction of the record company was, 'You shouldn't be smiling.' To me, that's bs. The first thing a baby does when it's born is cry and smile, I should imagine. And not cry because it's in any pain or is dismayed, it'll cry because it's a lease of life and it's 'Aaagh!' letting it out."

"I believe that when you get on stage it's such a good feeling between us that we enjoy playing," he said. "And we smile and fme, I will continue to smile. [Laughter.] We all will. But they have a thing like, 'You can't smile when you're playing the blues.' Why not? 'Well, you can't smile if you're talking about bleeding for someone.' It's that fine line, between smiling because you're enjoying yourself and smiling to the song."

That night at Butchertown, Smokehouse played for a small crowd that, in the end, demanded two encores. From the start, Arlon preened like a proud rooster, tossed his hair back and filled the room with electricity.

His stage mannerisms seemed completely unconscious, yet correctly soul-baring. After a set of watching Smokehouse, you get the feeling that you know Arlon – and his influences.

"Personally, with this band, I know that I have to tone down a bit," he said earlier. "I now that I over-sing and I know that I don't have to now work as hard as ... Like, in England, the band was so crappy, I had to stand up and burn all night. Like, seriously exhausted to try and keep the audience looking and receptive. That was the biggest comment made to me by [his father] Deke and other people is that, 'You don't have to do that now. You can relax and concentrate on singing it.' So that's apparent to me.' I don't have to do all that stuff."

It's unlikely that Arlon could turn it down whether he wanted to or not. A show is too much a release for him. Anyway, the rest of the band plans on meeting Arlon at the summit rather than have him scale down.

" ... It has become apparent that we have to do more to keep up with him because he's just up there bustin' a gut and just throggin' away," said Smith. "We watched a video [of a Smokehouse performance] and there's all this energy in center stage, you know and you look around and we're all boring and he's exciting. So we have to be more conscious of our performance."

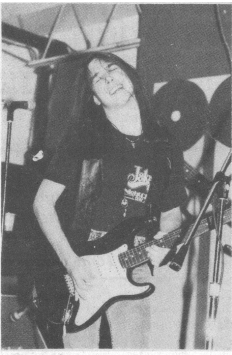

Smith speaks the truth, Arlon is a vortex of energy surrounded by comparatively pale band mates. But at the Butchertown gig, a change was already occurring. A new song written by Mingis, "Lemon Sun," was simply BIG, with the other musicians getting their due. Smith stepped out from behind the keyboards and joined Mingis on electric guitar and Thompson picked up a Bonham-like hammer of the gods, creating a thunderous rock crunch that challenged Arlon's dominance. Marston obliged with a steady bass line and some masterful falsetto singmg.

With "Lemon Sun," Mingis showed that Smokehouse isn't just the ideal vehicle for Arlon, it also is a brilliant showcase for him. The following song, a simultaneously touching and bruising tune called "Eden Street," allowed Marston to demonstrate his command over electronic effects. A Pastorius-like percolation bobbled the song along the bottom and Marston's skillful handling of the fretless added another dimension to the "soulful, new-era rock," as Smith described Smokehouse's music.

"Let's Roll" and "Road Inside" show one of the reasons for Smith's central role in the band, a role that Arlon likens to musical director. If all else fails, Smith's textures lift the sound to a place beyond the standard rock quartet, with the Yamaha CP-70 piano jauntily fighting off formula and rich swells from the Hammond beefing up the dynamics.

Not that heroics from Smith are needed to rescue Smokehouse's song list. It was Arlon's songs, remember, that attracted label interest in the first place.

"I think everyone would agree with me... . This is not meant to sound arrogant in any way at all, but looking down the set, there is not a song on the set list that I feel like, 'Maybe, maybe not," Arlon said. "We have a seriously hard time doing set lists. Every song to us, seems to have its place."

"When he came over, he had so many songs," Smith further explained. "And of the ones that we needed for a set - take all the songs that he had when he came over and take the kill-ER songs, we didn't even have enough room in the set to do all of So all that was left was the cream of the cream of the CREAM," Thompson said.

The songs are strong enough for an album. And the music is certainly ready for rock radio. In fact, Smokehouse's presence on the radio is overdue; there are several bands covering similar musical ground already and none are doing it as well as Smokehouse.

So what could possibly go wrong? The band members seemingly have just the minimum ego that is demanded by life in the spotlights ("You're more open to criticism because you are out there on the stage," said Arlon. "You are exposing yourself and you're exposing your feelings, you're exposing your talent to criticism"). The sound, so far, has been cohesive – no "artistic differences" seem imminent. And you can rule out drug problems.

"This is the straightest band that I've ever been in," Thompson said. Arlon, in addition to shunning drugs in his private life, attacks them in his song lyrics.

"'Eden Street' is about a girl on crack and heroin who goes cold turkey," he said. "'Rainbow Cloud' is about a girl who dropped acid. It's about a good friend of mine that I was in school with [who] left school. She was...every time I saw her, she was totally spaced. You couldn't have a conversation with her. She was kind of justifying her reasons for taking drugs and stuff. Saying that she didn't have enough money for beers and acid would work better for longer. You just see a friend of yours stop ... not being the person that you thought they were ... . That's why. I do have strong feelings about drugs because my parents always hammered it into me about drugs. Not to do it, obviously."

"My philosophy is that anybody can take drugs, drink and die for doing it," Arlon continued. "Nobody gets famous for that. If you can't do it without it, then you can't f do it, because it's something else making you do something. ... personally, I'd be terrified to take drugs if I was on stage. Oh man, I would be so scared of f–ing up . . . And apart from that, it's just not doing your job. So personally, I'm against it."

The five musicians are happy with their success so far, but they are facing forward, planning for patient growth. Thompson in particular said he feels it will take "at least 50 shows" before Smokehouse really starts hitting it's stride.

"It's getting there," said Thompson. "It's such an embryo right now."

"I don't think it will ever get to a point where it's done, either," added Arlon. "It's going to keep going."

Smokehouse recently recorded their set at Allen-Martin Productions, to be used as a demo by Imago. They plan on gigging for the next six months, but they say they are ready to do an album and have it completed by summer. It's the long haul, brother, and no one seems to expect overnight success.

So the band as a unit seems built to last. But what happens if the record company doesn't like it?

From my viewpoint, I believe the record company will pick us up," said Arlon. "But if it doesn't pick it up, I would have no qualms in leaving the record company and staying and doing this. Because this is what I've always wanted to do. This is the sound that I would die for. The personality of the band is just totally sunflower. It's beautiful.

I mean, everybody gets on and it's focused, with one will and everything is beautiful.

"This to me is it. Rather than a big record company saying that this is it. And I don't care if that's 'on the record."'