Like most musicians, Turley got bitten by the music bug early in life. "My Dad was a pipe fitter at Westvaco in Charleston, West Virginia," he recalls. "When I was 12, a neighbor threw a guitar away. I got it out of the trash. It only had three strings on it, but I was walking around hitting it wide open. This neighbor who played guitar heard me, and bought me a set of strings and put 'em on for me. I started teaching myself how to play. My brother Fred always had jazz and rhythm and blues in his record collection, so I got into the early stuff - Billy Ward and the Dominoes, Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters, Coleman Hawkins, Lightnin' Hopkins. I just got into it. I was not an Elvis Presley fan."

In an odd way, it was the civil rights movement which nudged Richards into playing professionally. "In 1955, when I was fourteen, they integrated our school. I remember coming to school that morning and there was this big group kind of circling around this wall at the side of the school. I asked what was going on, and they told me there were 'colored kids' here. I moved up into the circle and saw these nine kids, petrified, leaning against the wall with the entire school lookin' at 'em. So I went straight up to 'em and introduced myself to everybody and shook hands with all of them.

"I became really close friends with Jim Brewer, Jim Liefer and 'Hambone' Taylor, and just started singing with these black kids all the time. They invited me out to their church to sing, and there was one weird thing I couldn't understand at that age. When I went there, every person in that place came up and shook my hand and all that. Yet whenever one of my black friends would come anywhere with me where there were white people, they shunned him. I didn't like that at all, so as I grew older with those guys, I started marching on white swimming pools - I almost got shot by a guy who stuck a gun right in my face.

"We went back home about four years ago. My son got to meet Jim Brewer. When Jim saw me, he ran up the street, put his arms around me and just cried on my shoulder. He took my son, Adam, by the shoulder and said, 'If it wasn't for your daddy, none of us black kids up here on the hill would've finished school. Every time there was about to be a fight, your daddy ran in the middle of it and stopped it or fought for us.'

"Anyway, by ninth grade, I had those three black guys and another white guy together in a band called the Five Pearls, and we were singing doo-wop. I played guitar and sang lead. The local TV station had a little record hop, and they had me to perform on there one time. They got all kinds of letters, so I put together a band and played on there three out of four Saturdays. We'd travel throughout West Virginia. This was back in '58 and '59. In '59, I did have a record out on Fraternity Records called "All About Anne." That was a song I wrote - and it was a horrible song. I got some notoriety in the tri-state area - West Virginia, Ohio and Kentucky - but nothing really came of it."

But things were soon to start happening for Richards, as his interest turned toward jazz. "Jazz in Charleston, West Virginia," he remembers, "was 98% black. I used to go the Crazy Horse, a black club in Charleston, and started sitting in there all the time. So I learned all about singing jazz."

Like much of his career, Turley's first move to the big city followed a familiar pattern. "I went to New York in 1964 to be a jazz singer with a suitcase, a guitar and $87. I'd sing in restaurants for food, and look for girls who seemed to be by themselves, to see if I could sleep on their floor.

"One of the girls was in show business herself, and she introduced me to Norman Schwartz, who managed Stan Getz and Gary McFarland and a bunch of jazz people. He got me signed first with Verve, the jazz label. I hung out at the Village Vanguard and the Half Note. Drummer Max Roach called me - I can't use all the words he used - 'the great white scat phenom.' Dizzy Gillespie came in one night, and I jammed with him."

His jazz career, however, proved to be short-lived. "I was onstage at the Vanguard with the Mel Lewis / Thad Jones orchestra, who used to jam on Monday nights there. Somebody in the audience hollered at us to do some rhythm and blues, and Richard Davis, the bass player, suggested we do some soul. We picked a key and just vamped on it, and I did all this James Brown screamin' and soul stuff.

"Frank Mancini, the president of MGM - which owned Verve - was in the audience. He sent me a note saying he wanted to see me in the office the next day. I go in, and he's sitting there with Creed Taylor, the president of Verve, and later had a label called CTI. They spent the next three hours talking me out of jazz and into the blue-eyed soul thing because it was so big."

Richards' voice was notable for its soulful sound, which he attributes to spending so much time in black churches and around black performers. "My first real gig was in New York at the Cafe Wha? on McDougal Street in Greenwich Village for seven consecutive weeks with Richie Havens and Richard Pryor. But I don't know where that soulfulness really came from - maybe some of it from paying dues. Soulful doesn't mean black - it means dues. A guy wrote an article one time and described me as a singer with a tear in my throat. I don't sound black, but I phrase black, like black church people sing.

"In the sixties, record deals were mostly for singles. So I stayed there for one record, the Clyde McPhatter song 'Since You've Been Gone,' then moved to 20th Century for one album called The Many Souls of Turley Richards. I had three or four originals on it - I still wasn't a great writer."

The history of Richards' recording career becomes a long string of major label deals, great records and persistent bad luck. "I moved to Columbia and did two singles for them. One was 'I'm a Lonely Man.' I wrote that, and it was strictly Otis Redding R&B. It was played all over the country on black stations.

"Columbia got real excited, thinking they had a hit, and did a dumb thing. They put a 2-page ad in Billboard, Cashbox and Record World with a full-size picture of ol' blond-haired, blue-eyed Turley. It was like a light switch went off - all the black stations quit playing it." Richards, ever the equal-rights advocate, is quick to add, "I don't blame 'em a bit - the white stations were doing the same thing to the black artists."

Following that experience, "I left Columbia at 11:00 on a Tuesday morning, walked down the street to Kapp Records and was signed by 2:00 in the afternoon. Jack Wiederman was at Columbia when I was signed, and he loved me. He left Columbia to become the president of Kapp. So I just made a call from a phone booth, went in to see him and signed a two-single deal with them. No hits came out of that, though. I had a song called 'This Is My Woman,' fashioned to be like Gary Puckett. But it was bubble gum, and it just didn't work.

"I left there and kind of floated around. Then I signed a singles deal with Warner Bros. in New York. Somebody brought the president of Warner's L.A. office down to the Bitter End, where I was playing. He just freaked out, came back to the dressing room and said, 'I don't know what buffoon signed you to a singles deal, but you need an album. ' I went in the next day and signed a two album deal.

"We finished that album around November of '69. Out of that album came 'Love Minus Zero (No Limit),' which was a major hit for me. It made Top Forty Billboard, did great in England. Based on that album, I toured with the Moody Blues, Poco, Steve Miller, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple and Cat Stevens - a bunch of 'em.

"This was the beginning of my becoming a Christian. One of the songs - and I was not a Christian - was an Edwin Hawkins song called 'I Heard the Voice of Jesus.' My producer was Lew Merenstein, who had just finished the Astral Weeks album for Van Morrison. We finished the album, the band had left, and I asked Lew to put a mike on my guitar and voice, and I sang 'I Heard the Voice of Jesus.' I did this thing in one take, and I was shaking when I finished. I went into the booth, and Lew and the engineer, who were both Jewish, were crying.

"I went off on my tour with the Moody Blues, and got a cassette and cassette player in the mail. I put it on, and Lew had gone back into the studio and over-dubbed bass, tambourine, organ, guitar and 21 strings. It was one of the most incredible records - it made the Billboard Top 100 just on airplay. Al Kooper had a cassette of it and was taking it everywhere on his tours and played it for DJs at FM radio stations."

Once again, the record was mishandled by the label. "It was getting tremendous airplay, but it wasn't getting sold, because Warner Bros. kept editing to try to get it shorter. By the time the stations got the final edit, they'd already received three or four edits, and finally threw their hands up."

But the incident proved to be a pivotal one in Turley's career, the move from secular to Christian music. "That record was the beginning of my going to the Lord. Scott Ross, now with the 700 Club, had a thing in Freeville, New York, called 'Love In', one of the original hippie Jesus freak places. He invited me to come up and sing. I told him I wasn't a Christian, and he said, 'Oh, but you're gonna be. Just listen to your song - you can hear the pleading in your voice.' He called me once a week for six months, until I finally agreed to go sing just to get him to stop calling me.

I went up there and sang, and something kept tugging at me. I went back a second time. I'd moved out to Jersey, and was living across the street from these people who wanted to know if I could sing at their prayer meeting. I didn't want to, but I went over there and sang. My first wife had invited their speaker (famous author Arthur Katz, who wrote Ben Israel) to spend the night with us, and we stayed up talking. About 4:30 in the morning on May 4, 1971, I gave my life to Jesus."

The decision was a life-changing one for the singer. "I didn't like where my career was going, so I got a lawyer and got out of all my contracts: record contracts, publishing contracts, booking contracts and my management contract. And I started out singing for the Lord. One of my dear friends is Phil Keaggy, who was with a group called Glass Harp, also produced by Lew Merenstein."

Having some bad experiences with churches, Richards got discouraged, and came to Louisville. "An old friend of mine, Mickey Clark, who I produced over the years, had family here, and I came through and spent the weekend once with his family. I really liked being here, and I wanted to hide away.

"A guy named Eddie Donaldson, who had just seen me on the Carson show a few months before, had a club down on Washington Street, so I played there and started drawing a big crowd."

As it turned out, Richards was about to begin a new phase of his career, as a producer. "I started producing in 1972. I actually hadn't moved here yet; I was still down here sort of hiding away from the whole New York scene.

"Somebody said, 'Hey, you ought to go out and see our studio.' I'd been to all the major studios in New York, so going out to a little eight-track studio was kind of funny for me. I had never produced. I had assisted on one production. It was so funny - they all said, 'Hey, why don't you produce it? You're from New York.' Which I thought was pretty funny: Just because i wasn't from Louisville and was from New York City, I could produce a record.

As it turned out, they were right. "So I produced a couple of projects on three artists, two songs each: Becky Goode, Denny Lyle and Bruce Harris. I took it back to New York and found a small label that was really interested in signing all three of em. So I was real excited."

"I came back down to the man who owned the studio and he told me he was going to put them on his own label. That was the falling out for me and this guy – I felt like I'd done all this work for nothing and now he tells me it's on his label. That was my introduction to people running the music world down here."

Then came another twist and a new medium: television. "Rod Burbridge, who's now general manager of WGZB, was a buyer for WHAS and was coming in to hear me at these little clubs. He said, Man, you ought to do a TV pilot. I did and they couldn't sell it. I came back from a trip to New York and found Newell Fox, who at the time owned nine Burger Kings and with the help of a friend, I sold the show to him. That s how I had the TV show in the summer of '72, which I was co-producer of. It was a prime-time, half-hour show at 8 on Thursday nights, on WHAS-TV 11 and it did real well. I fell in love with Louisville, so I decided to move here for good."

Life remained unpredictable. "I was still on a hiatus as far as record labels and in '74 a small label in California called Calliope wanted me to produce a record on myself. They seemed like exactly what I wanted. I didn't want to be with a big label. So I went to California and produced this record only to have this label not only fold, but also not pay the bills on everything I ran up. Just another one of those crazy things – I'm thinking, God, are you sure you want me to produce?;

"Back in Louisville, I met the mother of my two kids (Adam and Amber) – Patty Kirchner was her name at the time – and we fell in love in '75 and got married. In '72 I did a couple of little things, including a live album called From Darkness to Light, recorded at Bellarmine College. I ended up selling about 8,000 of them over the years. It was just me and my guitar and it was a very avant-garde sounding Christian album. That's back when I was using all of my vocal range, which at that. time was five octaves.

"It was my first Christian music – you might say it was divided down the line between Christian and secular. From Darkness was the secular side and the two songs were called 'Ugly Trip' and 'Pain.' The Christian side was 'The Light,' where I could see. I think I had to go blind to really see. I was hell-bent to be dead by the time I was forty years old, with the life I was living.

"I'm proud of one thing. No matter where I sang, whether it was a major concert, at a bar or a private party, I still did Christian songs too – not gospel songs, songs I had written, like the 'Voice of Jesus' song that did so well."

As any musician can tell you, real life has, a way of dictating career moves. "In '76, when I found out Patty was going to have our son, I knew I needed to be doing something other than singing in little clubs. I produced a project on myself and sent it out to ten record labels, which is nothing I would ever tell anyone to do, because you should never do wholesale mailing. But I figured since I'd had two albums on Warner Bros. and one on Twentieth Century, people would know who I was.

"I was flabbergasted. I had 100% response. All ten labels wanted to sign me. It blew me away. You talk about your ego jumping to the ceiling! You re thinking, Hey, God, I don't know if I need you or not. I'm pretty strong!' Your ego kicks in. E – G – O: Edge God Out.

"I decided on Epic Records, because it was in Nashville, which was only 180 miles away. I didn't equate it with country. When my record did come out, it was stuck in a lot of country racks in record stores, because it was written down in Nashville. This was before Nashville became the big mecca that it is today. Anyway, I did the first album, West Virginia Superstar. I still wasn't producing then, although I did produce a coupleacts in '76:" a groud called Country Folk and another called The Cumberlands."

But as had already happened so many times before, problems lay ahead. "In '77, after the album came out, some things happened that probably shouldn't have happened with Epic Records and my producer at that time, Mike Post (L. A. Law, Hill Street Blues, Rockford Files, Law & Order, all TV themes). The label wanted Bobby Colomby to produce me. He was the drummer for Blood, Sweat & Tears and was someone at CBS that they all wanted to do things with.

They wanted to replace Mike Post with him and I wouldn't let 'em. I thought Mike had done a good job. He'd done what they asked for, but they didn't care. They were just gonna axe him and have me with Bobby Colomby.

"My friendship with Mike had gotten so tight, I just said no. They said, either you let us do that, or we'll drop you from the label. I said, whatever you feel like you have to do – but I'm not doing it. So they dropped me.

But they gave me $25,000 when they dropped me – had a little bit of guilt, didn't they!" But even as Richards' recording career seemed at an impasse, his career as a producer began to bloom. "I started dabbling a little bit more in production and in 1978, Gil and Jo Whittenberg (Gil was the contractor in Louisville who restored the Seelbach) financed me a production company. I started producing some people around town. I produced one group called Midnight Star, who turned out to be a huge success – but not through me. After I tried to get 'em a couple deals, they ended up going with Solar Records and I was not a part of that package. But I did produce them on a local basis.

"I produced a group called Sundown Red, which is Steve McNichol and his brothers and got them a deal on 20th Century. Unfortunately for them, while we're in the studio recording their fourth song (we had a very good budget at the time? $30,000 for four songs), the president of the label stepped down. Another guy took over and the first thing he did was go down the roster and eliminate all these groups – and they were all rock groups, So they were dropped in the middle of recording their first record for 20th Century.

"I also produced a girl named Mary Welch for 20th Century and I had two hits with her: a disco version of "I Could Have Danced All Night" (I hate disco) and a middle-of-the-road, Barbra Streisand-type song. I can't recall the title, but both of them made the Top Forty in their respective charts. I produced a group called South Shore, from South Bend, Indiana. I had Bearsville Records ready to sign them to a very lucrative deal, when the two writers in the band got in a huge fight and the band broke up."

As he recounts his early production experiences, Richards laughs. "I was starting to think that I didn't need to be doing this – that I should be doing something else. Mr. Whittenberg said, Turley, why don't you produce yourself?' But I didn't know; it's one of the hardest things in the world to do.

"I told him we couldn't do a little $4-5,000 demo; they expect more out of me in the record business, cause I've been there. He asked what it would take and I told him at least $25,000. Next day in the mail, there was a $25,000 check.

"I went on to produce the record and I produced it totally different. Because I have such a rangy voice, producers had always felt they had to compete with my voice (with the arrangements), when in fact, they should have kept the tracks more simple and allowed me to do what I do. I had read that Paul McCarney put a metronome down while he played piano, then came back and played bass on it and drums on it. So I put the metronome down with me playing guitar.

Once I had all the guitar parts down, I came back and sang on it. Then I came back and did all the background vocals. On one song, I did 36 background vocals; I just kept stackin' 'em.

"I took that tape to Nashville and hired a five-piece band to play with what was on tape. They could create, but within my parameters. So as soon as my vocals and guitar were on there, I eliminated Turley the artist, so I could then become Turley the producer. Then I was removed from that singer and could just deal with this band's creation of making what I already had on tape sound better.

"That album was called Therfu and had a hit record called, 'You Might Need Somebody.' I went out to L. A. with it and had three labels wanting to make a deal with me: 20th Century, Portrait Records and Infinity. For me, they were all offering very nice budgets – $80,000 budgets, $25,000 signing bonus, some money to live on and some other things."

But Richards was about to pick up a very influential benefactor. "While I was there, I found out an old friend who used to be with Warner Bros., was working with the Fleetwood Mac organization. I wasn't a Fleetwood Mac fan, but I knew who they were.

"I went over and played the tape for her and she flipped out. She said, You've got to let Mick hear this. 'I asked, Mick who?' She said, Mick Fleetwood!' She sent the tape out to his house that night. Early the next morning, I got a phone call asking if I could come out to his place. They sent a limousine to pick me up. I went out to his house in Bel Air and stayed there all day long. We ate together, talked, played the music and got a really neat camaraderie together. I felt real secure at that point and he wanted to manage me.

"Being a businessman, I figured that, like this guy or not (and I did like him), he had a lot of clout, because Rumours was already around 30 million albums. I was introduced to his attorney, and they asked me what labels I was interested in. I told them the three labels I wasn't interested in, one of which was Atlantic Records – I won't go into why."

Here things start to get complicated. "A week later, I get a phone call from Mick's attorney, Shapiro in New York, telling me I had a deal if I wanted it. I asked him with who and he said it was Atlantic. I reminded him that they'd been on the list of labels I didn't want, but he asked me to hear him out.

"He said that (Ahmet) Ertegun (CEO of Atlantic Records) loved my stuff and was offering me a 6-album deal, $175,000 each for the first two albums. This was funds, not budgets, which meant if I recorded it for $50,000, I keep $125,000. The third and fourth albums were $225,000 each and the fifth and sixth were $275,000 each. That was huge back then – about like $800,000 now.

"He said he could get me 13 points, a retroactive 14 points at a million and 15 points at 2 million. I asked how he could get me a deal like that – it was the kind of deal they offered to stars — and he just said, They love you. ' So I wasn't gonna argue. I called A1 Schleschsinger, my attomey and he about hit the floor. We went over everything with a fine-tooth comb, but the contract was perfect. I didn't even have to sell a set number of records. I was on my way!"

As you might imagine, the picture wasn't quite as rosy as it first appeared. "After we finished the album, the release date was supposed to be May of '79. It got stopped and I got a phone call that there were some problems going on and they were going to pull out of the deal. That's when I found out what had happened.

"Shapiro had promised Atlantic a solo album from Stevie Nicks and didn't even have the power to do that. They just used that to get my deal. When Ertegun talked to Stevie about it, she referred him to her attorney, who informed them that they hadn't even had the right to offer.

"Ertegun was furious. He's like (Arista Records') Clive Davis; they're the two broken spokes in the business. Really odd people and just humongously successful. And if they don't like what you've done, you're gone. They don't care who you are. I could've been Barbra Streisand and they would have thrown me out the door.

"He said that they weren't releasing my album, so we asked if we could shop it around (to other labels). That way, they d get their money back and we'd be out of their hair. Ertegun was so angry, he said we could try it, but we had to get the exact same deal that l'd gotten from him. We shopped it around and all the labels were interested, but for nowhere near that kind of deal. The highest I got was $125,000 for a budget.

"So there I was in the middle of this argument. I came back and said we couldn't get this kind of deal and he said that we needed to renegotiate. He said I had to sell 100,000 on the first album, or they wouldn't pick up the rest of the contract."

That was fine with Richards. "The next day we were up at Mick Fleetwood's house with his attorney and everybody sitting on telephones. They called Ertegun to tell him what they were going to do. They said, Turley was going to tour with us, but now that the album won't be out, he can't, because he won't have any product to sell. But we're gonna take him with us anyway and Mick's gonna go in all the radio stations and he's gonna have his arm around Turley and tell everybody that Turley's the best thing since orange juice.'

"That got Ertegun all fired up again. They did press conferences and all these kinds of things. Unfortunately (and Mick will be the first to admit this happened) he's clean now, but his problems with certain kinds of drugs caused him to sometimes not go to bed until 8 in the morning and not get up until 5 in the afternoon. So he never followed through with going in to any of the stations. I met jocks at the concerts I went to, but he never actually went into any of the stations with me.

"That infuriated them again. But something happened that I didn't know at the time. My record had come onto the charts and it was blasting like crazy. It was up to 54 with a bullet – I mean it was flyin'. Then all of a sudden it didn't report the next week. The week after that it was 92, and the week after that, it was out of the Top 100."

Richards and Fleetwood were mystified. "It just doesn't happen like that. Everyone knows that records don't drop that fast. Not when it came in at 89, went to 78, went to 69, went to 58, to 54 – and bullets all the way up. Then all of a sudden, gone!

"None of us knew what had happened. We'd never seen a record die like that before. We made a joke – it went out of the charts with an anchor! But six months later, a guy left Atlantic who was head of promotions at the time. I ran into him and he said he felt so guilty that he had to tell me something.

"He said that the powers that be pulled the plug on any promotion of the record.

"And it was done. Nobody pushed it a single bit after that. I found out six months later," Richards recounts, admitting that he only made things worse. "I was so angry that I didn't think straight. I had two months left and I had put $67,000 in my pocket when that album was done. My album was at 93,000 in sales. I had that money in the bank. I could've gone ahead and bought 7,000 albums at $5 each wholesale, which would have made it l00,000 in sales by the deadline. He would have had to commit himself to the five remaining albums.

"But I waited too long because I wasn't thinking. That's where ego can really mess you up. In fact, at that point, I probably could've gone to Ahmet and said, This is between you and them. You like my material; let's you and I do something. ' But I didn t do that and I should have."

Still, the album gave Richards' career as a producer a much-needed boost. "That album got me tremendous reviews on my production ability. I took that and started producing artists. I'd been doing stuff in Nashville. I produced country singer Mickey Clark and a bunch of people from 1978 to 1981. Most of my production happened during that time. I did four Christian albums: Carman's live album Sunday's on the Way; James Ward's Faith Takes a Vision album, which had six out of nine songs being played on the radio and made the Top 10 in CCM on radio play alone; Ed Ratzloff's Drivin' Wheels, sort of a southern rock album; and a girl named J. J. Lee whose album was never released due to contractual problems."

Richards soon found out that even Christian music has its share of problems. "During this period, I began experiencing something that really bothered me: that the Christian record market was corrupt. I wondered how these people could do what they were doing in the name of God. I became holier-than-thou, which I had no right to do and said I wouldn't deal with these people anymore. Contracts were being set up in such a way that artists would never be able to make at penny – the labels would make all the money."

But there was still work available. "Back then, they had what they called a 6-to-1 write-off. You had all these rich people in the southeast investing all this money into venture capital, including music. That died down in 1984, when the IRS came down in Rolling Stone and said that they were going to start scrutinizing all the music venture capital and anywhere they found a discrepancy of any kind, they were gonna go back ten years for each investor. So that stopped just like somebody turned a light switch off. And that's how independent producers survived at that time."

Then Richards' performing ability began to suffer. "In 1984, I started having some vocal problems. For all intents and purposes, I lost my voice. I could sing maybe one set or two sets in one night, then the next night I could hardly sing at all. I'd have to lay off and then three nights later I could do another one or two sets. I couldn't perform anymore, so my income went haywire.

"I was fortunate enough to be able to open for the Pointer Sisters, which meant I only had to do a thirty-minute set. I did a Ray Charles concert – again, another 30 or 40 minutes."

The years that followed were a mixed blessing. "Nineteen ninety-one was the turning point, but which actually began when I married Diane Ray in June of '88 and five months later my son came to live with us. A year later my dad died, and Diane took my mom in – both my son and my mom without batting an eye. Diane's quite a lady. She brought a lot of balance to my life. We joined Southeast Christian in 1989 and we were baptized. Then in '91, Mom died. That seemed to be the time when I really needed to turn my life over to God. I cut a good album and shopped it to Christian labels."

If it seems that Richards has held up well after going through the music business wringer, we should mention one other fact.

He s blind.

"At age 4 1/2, I was accidentally shot in the left eye with a bow and arrow. The doctor should have removed the eye immediately, but he didn't and problems spread from the left eye to the right eye. We were very poor and the people got money together to send me to this major surgeon in Cincinnati. I didn't get to start school 'til I was 8 years old, because of my eye problems. I had eight operations by the time I was l7. At 21, I got a contact lens. Being a kid with vision problems and not being able to do what I was really good at, which was play basketball, having music to fall back on really helped my pride. Then I got the news in '68, at age 26, that I was going to lose the vision in my other eye. It was supposed to happen within six months, but it took about a. year."

Amazingly, only once in his life did the singer ever consider quitting and that single incident came about less because of his blindness than his young age at the time. "At age 20, I took off for California with an organ player and a, drummer to become a star. I bought the car and we drove out there.

After two weeks, the other guys got regular jobs and said they were giving up music. So there I was stuck with the car and I couldn't see to drive. Thank God, I had a brother and sister out there, so I stayed with my brother for about three months, then sold everything there and came home."

Richards' career was literally saved by a devoted mother. "I was angry and told my mother I was never going to sing again. I grabbed a basketball and left. I came back about five hours later and there was another guitar laying on the bed. And we were poor.

I said, What are you doing? We can't afford that!' She said, If you sell that one, I'll buy another one. Sell that one, I'll buy another. You're going to be a singer, because you're going to have to be. With your vision problems, you're going to have to have something to fall back on."'

Which is not to say that making the transition to being sightless has been easy. "Even after being saved, I was still dealing with it. I finally got control of what the blindness was in my life. I got in front of a mirror and said, You used to live on a two-way street; now you live on a one-way street. Where's the personality you always had before to make people smile and laugh? Let's stop riding the pity pot and get to work!' From that day on I started making jokes about my blindness. I started realizing that what it did was make people comfortable."

Richards clearly recalls how his blindness affected the thought process he went through in 1991 as he prepared his album for submission to Christian labels. "Now if I'm a businessman sitting on the other side of the desk looking at Turley Richards, thinking the way they think, I'd say,"There's a lot we can get out of this. Turley's blind and we can do something with that. He's been a secular singer with hit records. He's performed with all these people. He'd be a great Christian act. I'd sign him immediately."'

That's not how things happened. "Not only did I not get signed, I didn't even get callbacks. I got maybe one or two verbal turn-downs, out other than that, I didn't even get a response.

"My old ego would have gotten angry and fallen apart, wondering who these guys think they are. But I just kept saying, It's God's will and whenever it's His time, he s got something special for me.' I've spent the last four years walking in that faith and I haven't wavered.

"Now I'm kind of scared, 'cause things are starting to cook right now. I'm asking people to pray for me, that I don't start trying to run ahead of God again, that I still stay in His will and allow Him to orchestrate what s going to happen. My personality is to lead. As soon as this stuff starts to happen, I know all the tricks for getting things done. But He does it better than I could ever do it."

•

Scott Hall, President of the local Axiom Music Group, has this to say about Richards: "Although on the surface it may seem that Turley' s life has been filled with tragedy and pain, he remains positive and upbeat, especially regarding his plans for the future and he attributes it all to the grace of God."

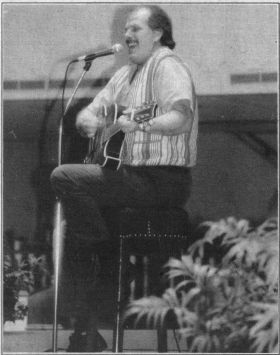

You can see Turley Richards in June at the following venues: June 2 at 7 p. m. at the Buck Grove Baptist Church on Buck Grove Rd. in Ekron, Ky.; on June 10 at7 p. m. at the Kentucky Center for the Arts in Louisville as part of "Stop the Violence, Start the Harmony"; on June 11 at morning service at Fem Creek United Methodist Church in Louisville; and at his booth June 24 at Joy Jam in Cardinal Stadium. Call venues for exact times for all events.

To contact Turley Richards regarding his merchandise (CDs, cassettes and video) or for his services as a producer, or to book a concert or for consultations on any of the above, including songwriting and vocal coaching, call (in Louisville area) 231-0387; outside of Louisville, call 1-800-269-1225.

Or write: Turley Richards Music Ministry, 2419 Westwood Ave., Louisville, KY 40220.